Private Forms of Money and the State [Part I]

On the intricacies of historical forms of private money such as bills of exchange to those of modern cryptocurrencies and their relation to the evolving roles of financial institutions of states

Image created with Apple Image Playground and Bazaart (2025).

Private forms of money have a long and broad historical track record and evolved alongside public legal tender. The nature of their entanglement has been and is being shaped by their specific historical circumstances. Depending on this nature it can be acknowledged that the extent of the one having influenced the development of the other as varying but still recognisable. While some forms of private money are rather ephemeral in terms of their capacity to inform new social practices of money, others have managed to leave behind their customary origin of the private economic sphere and reach near the top of the monetary hierarchy or even transcended in to a totally new hybrid form of money. In the following [Part I] shall be shown how private monies can be characterised vis-à-vis public money. Additionally, it is to be explained how private forms of money have shaped public forms of money and vice versa, i.e. how monetary and fiscal policy developments of states (together with the unfolding un/intended consequences in the economy) have given rise to new forms of private money [Part II].

Previously, it has been established that money is an important political matter that is often misrecognised and disguised as a natural social fact of life. It is however the case that

“[t]he ‘money question’ lies at the centre of all political struggles about the kind of society we want and how it might be achieved.” [1]

It has moreover been established that money has evolved in the form of various hierarchically distinct forms with ‘the more substantive means for final settlement of payment obligations on the top and the less potent ones towards the bottom’. [2] It is therefore relevant to once again ask: what counts as money? And can a meaningful distinction be made between private forms of money and public forms of money?

Attempt at characterising private forms of money

To answer this set of questions, it is worth to first give credit to the argument that ‘financialization is marketization’: [3]

“New markets with a trade in new products, mostly unregulated or lightly regulated, and the resulting opacities and lack of pricing transparency allow for fees, commissions, tricks, and speculation. In the early days of new forms of money, business deals are possible for the avant-garde that are not yet available to others.

What counts as money and what does not matters for these practices of profit generation, because the transferability of all kinds of financial instruments into state money (reserves), bank or credit money (deposits), or other forms of money (liquid securities and derivatives) is an important strategic component of profit-making. If a varied portfolio of different financial instruments, a.k.a. money forms, were not essential to profit generation in times of asset and liability management, moneymakers could simply rely on old-fashioned cash or bank-created deposits tout court. But they don’t, because new money forms allow them to hedge risks, to speculate on the future, and to repackage and sell existing assets; they make expected earnings monetizable and capitalizable, and thus allow for further trade and exchange profits that cash would not offer. Moneyness is thus a strategic factor in profit-making and capital accumulation.” [4] (original emphasis)

By summarising the passage above, private money can thus be defined as and linked to:

unregulated or lightly regulated practices of financial innovation;

rather exclusive financial instruments;

the repurposing of or design of new revenue streams leading to the capitalisation and monetisation of previously unimaginable objects and/or purely mathematical (abstract) constructs;

in order to increase profitable opportunities in the present.

Entanglement between the economic and political sphere

This drive to seek new profitable opportunities is commonly being associated with private enterprise, but not exclusively so. If profit-making is understood as an activity to increase power, then states have historically also shown to be strategic actors engaging in financial innovation in order to benefit in a rather geopolitical sense:

“access to credit was important for European states. […] The ability to borrow was critical in medieval and early modern Europe because it allowed states to participate in wars, either defensive or offensive. [As] money had become ‘the obligatory link between authority and soldiers’, [t]he ability to raise funds by borrowing clearly had enormous advantages for European states in an era of incessant warfare.” [5]

So this shows once again, that money did not come into the world to overcome the difficulties and inconvenience of barter, but has, like any other human institution, grown to satisfy various needs of private enterprise and polities entrusted with power alike. [6] The desire to engage in activities of profit-making is nonetheless a modern phenomenon connected with capitalist development:

“capitalism is a system that demands constant, endless growth. Enterprises have to grow in order to remain viable. The same is true of nations. […] What was once an impersonal mechanism that compelled people to look at everything around them as a potential source of profit has come to be considered the only objective measure of the health of the human community itself.” [7]

In order to explain how private money is different to public money, it helps to introduce two further conceptual pairs.

Distinction of Special- and General-Purpose Money

Anthropologists have come up with the idea of distinguishing between general- and special-purpose monies, so to draw conceptual boundaries: special-purpose money includes merely a limited set of goods and services (if at all) whereas ‘general purpose money […] enables one to buy a far greater range of goods and services’. [8] This distinction envisaged by Paul Bohannan in 1959 served to understand the consequences ‘of introducing new ways of obtaining prestige, status or power into traditional societies’, which created ‘a situation of status conflict’ within these societies. [9]

Distinction between Commodity-Money and Fiat-Money

Another relevant distinction worth to mention in this context is the one between commodity-money and fiat-money. Commodity-money is regarded as featuring intrinsic value. It is ‘composed of actual units of a particular freely-obtainable, non-monopolised commodity which happens to have been chosen for the familiar purposes of money, but the supply of which is governed — like that of any other commodity — by scarcity and cost of production’. [10] Fiat-Money, as opposed to commodity-money, ‘has no fixed value in terms of an objective standard’ [11] and ‘is emitted by […] declaration’. [12]

The table below summarises David Graeber’s scheme on the cyclical history based on the use of commodity- or debt-money in a ‘vastly simplified’ way to make sense of their co-motions over the long run. [13]

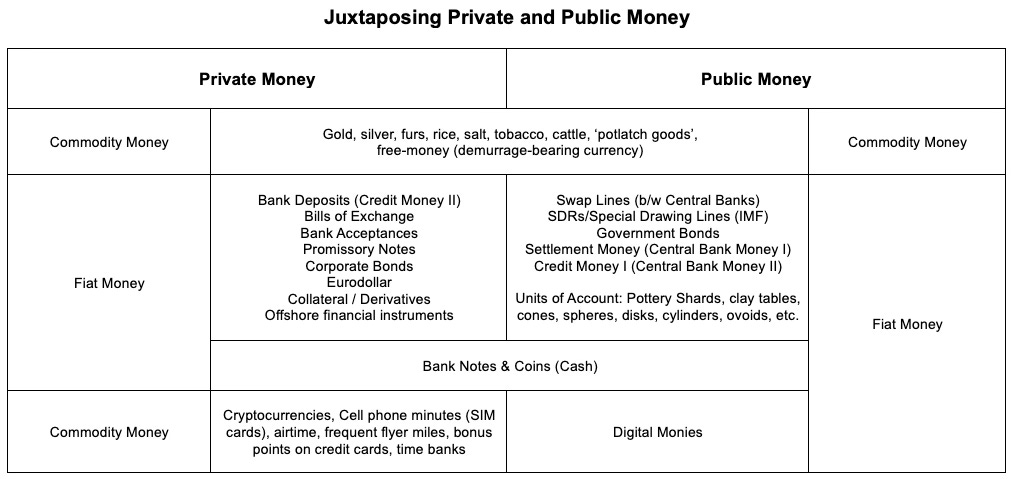

Juxtaposing private money vis-à-vis public money

The table below juxtaposes private money and public money. It again is a very simplified sketch as some particular forms of money have functioned as both private means of settlement as well as accepted as legal tender over the course of time. For instance, commodity money (such as gold, silver, furs, etc.) counted at first as some sort of ‘customary tender’ used for payment purposes or to increase the prestige of the ones engaging in economic activity (like in the potlatch practice of particular indigenous peoples). The same goes for free-money that are usually set up for the special purpose to reactivate local economies by private and community initiatives. Quite of few of these have gotten to be accepted by public authorities:

gold is used by central banks to back up their currencies;

local or free-money such as the Bristol pound or the Chiemgauer managed even to be backed-up by public money and served their regions as a complementary currency.

Other private (or community initiatives) failed to be implemented due to lack of support from political or public authorities: the demurrage-bearing currency in Wörgl in Austria was introduced in 1932 as a tax to benefit the unemployed but was not allowed to continue only 2 years later, as the Austrian National Bank did not allow for complementary currencies in the country.

Fiat-money can also provide many examples for producing private ‘customary tender’ (like bank notes that were issued by private banking) and over time became ‘legal tender’ issued by central banking systems. Up to this day, Scottish and Northern Irish banks are still allowed to emit their own bank notes but they must reconcile that with the Bank of England). Bank deposits, bills of exchange, promissory notes, corporate bonds, collateral and derivatives as well as offshore financial instruments are further examples of private money. The acceptability as legal tender depends historically on the severity of the crises they are prone to provoke as central banks and parliamentary assemblies and governments make the final call on whether certain asset classes possess the legal quality at all. However, history has shown that it may also depend on the power of certain interest groups that are able to influence political decisions in their favour — and to save the public monetary system (see the argument of systemic collapse and big banks being “too big to fail” after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008/09, GFC). [14] Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, have developed as a reaction by private entrepreneurs in response to the GFC triggering in turn the development of digital public money such as the “digital euro”. This shows that private and public money endure an intertwined existence. [15]

Sources:

[1] Ingham, G. (2020) Money, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, p. 8

[2] Barta, A. (2023) ‘What is money? Brief overview of its characteristics, key functions and substitutes’, [online] available at: <https://alexanderbarta.substack.com/p/what-is-money> [Last accessed on 28th August 2025].

[3] Godechot, O. (2015) ‘Financialization is marketization! A study of the respective impacts of various dimensions of financialization on the increase in global inequality’, in MaxPo Working Paper 15/3, Paris: MaxPo– Max Planck Sciences Po Center on Coping with Instability in Market Societies,.

[4] Koddenbrock, K. (2019) ‘Money and moneyness: thoughts on the nature and distributional power of the 'backbone' of capitalist political economy’, in Journal of Cultural Economy, p. 10, [online] available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2018.1545684> [Last accessed on 28th August 2025].

[5] Stasavage, G. (2011) States of Credit: Size, Power, and the Development of European Polities, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 25ff.

[6] Young, A. (1929/1924) ‘The mystery of money: How modern methods of making payments economize the use of money. The role of checks and bank-notes’, in The Book of Popular Science, New York, NY: The Grolier Society, pp. 265-276. See also Barta, A. (2023) ‘On the Origin of Money: Origin myths and corresponding theoretical development’, [online] available at: <https://alexanderbarta.substack.com/p/origin-and-evolution-of-money> [Last accessed 28th September 2025].

[7] Graeber, D. (2021) [2011] Debt: The First 5,000 Years, 10th Anniversary Edition, Brooklyn, NY: Melville House, p. 346.

[8] Di Muzio, T. and Robbins, R. H. (2017) An Anthropology of Money, New York, NY: Routledge, p. 6f.

[9] Ibid., p. 8.

[10] Keynes, J.M. (2011) [1930] A Treatise on Money, Mansfield Center, CT: Martino Publishing, p. 7.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ingham, G. (2020) Money, Cambridge: Polity Press, p. 64.

[13] Di Muzio, T. and Robbins, R. H. (2017) An Anthropology of Money, New York, NY: Routledge, p. 17.

[14] Pistor, K. (2019) The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[15] Tropeano, D. (2025) ‘New Private Forms of Money and the State’, in International Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 54 (2), pp. 231-244.

Complementary addition: The national supervisory authorities, the European supervisory authorities for banking supervision (EBA), insurance (EIOPA), and securities and financial markets (ESMA) have jointly developed an interactive information sheet and published it in all EU languages. The information sheet features pop-up boxes that explain technical terms in a simple and easy-to-understand way. It also provides an overview of which crypto-assets are regulated under MiCA (<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markets_in_Crypto-Assets>) and which are not: <https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2025-10/0b10e48a-1a95-404c-b771-8bdb6503aac1/Updated%20Joint%20ESAs%20Factsheet%20on%20crypto-assets_EN.pdf>