Since the previous interrogations focused primarily on the theories of money creation, it was not especially being defined and discussed yet, what its fundamentals actually are.

“There is no denying that views on money are as difficult to describe as shifting clouds.” [1]

Money has long accompanied societies over many centuries and taken on various forms. [2] It plays an influential role in how everyday life is structured in a given society and has itself evolved at various points in history.

A modern textbook definition of money goes along the following lines:

“Money […] is defined as anything that is generally accepted in payment for goods or services or in the repayment of debts.” [3]

For this to be the case, money must be a highly liquid asset class, that is usually instantly available and generally acceptable in exchange for goods and services or to settle debt relationships.

Characteristics:

highly liquid

usually instantly available

generally acceptable as a means of final settlement

However, this obscures major unresolved disagreements over what money constitutes. As already outlined earlier, there are seemingly diametrically opposed analyses of banking, linked to the difficulty of clearly distinguishing money from credit.

Two conceptualisations of money:

For one, money is a ‘neutral’ commodity like any other:

“‘Commodity-exchange’ theorists [viewing] bankers as intermediaries collecting small pools of money from savers and lending it from the accumulated reservoirs to borrowers.” [4]

For others, namely the ‘claim’ (or ‘credit’) theorists, money is:

“precisely a ‘mental estimation’: that is, a socially and politically constructed abstract value.” [5]

As Georg Simmel immortalised this thought in his Philosophy of Money as follows:

“[M]oney is only a claim upon society […] the owner of money possesses such a claim and by transferring it to whoever performs the service, he directs him to an anonymous producer who, on the basis of his membership of the community, offers the required service in exchange for the money.” [6]

In order to understand how viable monetary systems persisted and were guaranteed over time, there can only be ‘definite social and political conditions of existence’ that allowed for their continuous evolution. [7] It is an ‘institutional fact’ with ‘constitutive rules’. [8] So one is able to infer that ‘money is a creature of legal order’. [9]

Key functions of money:

measure of value / measure of prices / unit of account

treasure / means of storing and transporting of abstract value

means of final settlement (of debts) / standard of deferred payments

means of circulation / medium of exchange

means of payments

Money is thus being constituted by performing the above functions ‘that are assigned socially and politically’:

“Money is uniquely specified as a measure of abstract value (money of account) […]; and as a means of storing and transporting this abstract value (for means of final payment or settlement of debt) […]. All other functions — medium of exchange, for example — may be subsumed under these two attributes […].” [10] (original emphasis)

Continuum of liquidity comprising money, credit and monetary substitutes:

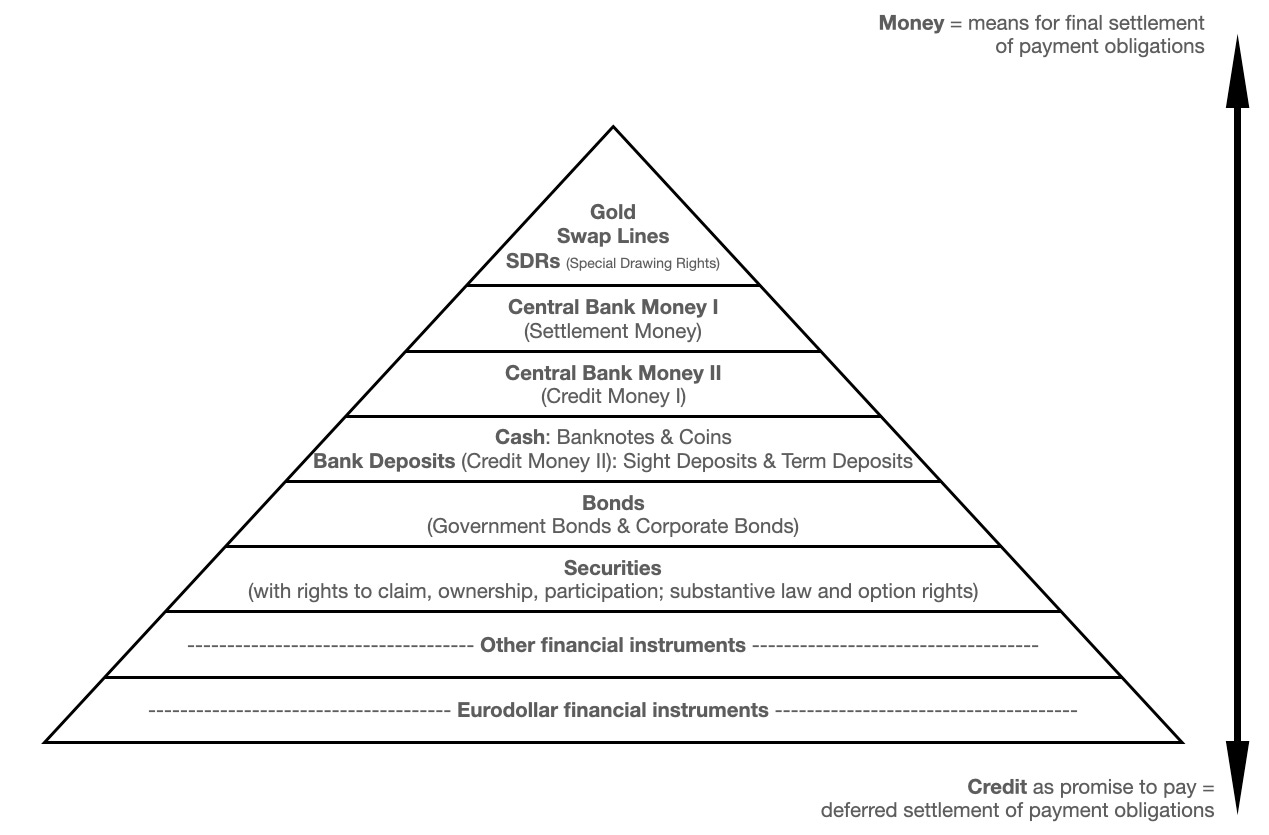

The above pyramid illustrates the so-called hierarchy of money by situating the more substantive means for final settlement of payment obligations on the top and the less potent ones towards the bottom:

“gold [or access to swap lines; special drawing rights, for instance] is the ultimate money because it is the ultimate international means of payment, and national currencies are a form of credit in the sense that they are promises to pay gold [or to access swap lines; use special drawing rights to settle payment obligations]. National currencies may be ‘backed’ by gold, in the sense that the issuer of currency holds some gold as reserve, but that doesn‟t mean that these currencies represent gold or are at the same hierarchical level as gold. They are still promises to pay, just more credible promises because the presence of reserves makes it more likely that the issuer can fulfill his promise.

Farther down the hierarchy, bank deposits are promises to pay currency on demand, so they are twice removed promises to pay the ultimate money, and securities are promises to pay currency (or deposits) over some time horizon in the future, so they are even more attenuated promises to pay. Here again, the credibility of the promise is an issue, and here again reserves of instruments that lie higher up in the hierarchy may serve to enhance credibility. Just so, banks hold currency as reserve, but that doesn‟t mean that bank deposits represent currency or are at the same hierarchical level as currency.” [11] (incl. own notations)

Dealing with gold and negotiating swap lines are first and foremost within the purview of central banks to settle international payment obligations. Special Drawing Rights (in short: SDRs) were established and are managed on behalf of governments within the institution of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that can be considered as another means of settling international payment obligations. Central bank money I (settlement money) stands for the clearing between commercial banks and central bank money II (credit money I) is issued as part of the government bond emission process. Credit money II stands for bank deposits that are issued as part of the creation of book money during the loan origination by commercial banks.

This graphic also shows the crux of where to draw the line between what counts as money and what counts as credit. It draws attention that liquidity implies in essence both the natural scarcity of ultimate money (as embodied in the currency principle by “commodity-exchange” theorists) and the natural elasticity of derivative credit (arising out of the banking principle argued by “claim or credit” theorists):

“The natural scarcity comes from the fact that agents at any particular level in the hierarchy cannot by their own actions increase the quantity of the forms of money at a higher level than themselves. Just so, governments cannot increase the quantity of gold, and banks cannot increase the quantity of government currency. The availability of money thus serves as a constraint that holds the system back in its attempts to expand.

The natural elasticity comes from the fact that agents at any particular level in the hierarchy can, by their own actions, increase the quantity of forms of credit at their own level, and possibly also below them. […] The elasticity of credit thus serves as an element of freedom that facilitates breaking loose from any constraint that may be standing in the way of expansion.” [12] (own emphasis)

What the above continuum additionally shows is that money is not only a technical device whose supply is only to be managed by economic experts. Money is not being entirely controlled autonomously by central banks but is also being affected by the balances of payments and the external exchange rate as well as determined by the lending activities of commercial banks depending on their market constellations (so-called endogenisation of the money supply). [13]

At the root of it, money has a dual nature:

“money is not only ‘infrastructural’ power, it is also ‘despotic’ power. In other words, money expands human society’s capacity to get things done, but this power can be appropriated by particular interests. This is not simply a question of the possession and/or control of quantities of money — the power of wealth. Rather […] the actual process of the production of money in its different forms is inherently a source of power.” [14] (original emphasis)

This dual nature of being a source of social power and a means of control implies that money does bring about effects, such as benefitting not the general public but only a certain group of individuals. This is why, as was the essence of an argument on economic imaginative power, that 𝄆 Money = Political 𝄇:

“The ‘money question’ lies at the centre of all political struggles about the kind of society we want and how it might be achieved.” [15]

Sources:

[1] Schumpeter, J. A. (1963/1954) History of Economic Analysis, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

[2] Di Muzio, T. and Robbins, R. H. (2017) ‘Theory, History and Money, in An Anthropology of Money, New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 43-76.

[3] Mishkin, F. S. (2013) The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets, 10th ed., Essex, UK: Pearson, p. 49.

[4] Ingham, G. (2020) Money, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, p. 10.

[5] Del Mar, A. (1901) A History of Monetary Systems, New York, NY: The Cambridge Encyclopaedia Company.

[6] Simmel, G. (1978) [1907] The Philosophy of Money, London: Routledge, pp. 177-178.

[7] Ingham, G. (2004) The Nature of Money, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, p. 70.

[8] Searle, J. (1995) The Construction of Social Reality, Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, p. 13.

[9] Knapp, G. F. (1905) Die staatliche Theorie des Geldes, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, p. 1.

[10] Ingham, G. (2004) The Nature of Money, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, p. 70.

[11] Mehrling, P. (2012) The Inherent Hierarchy of Money, p. 2, [online] available at:<https://sites.bu.edu/perry/files/2019/04/Mehrling_P_FESeminar_Sp12-02.pdf> [Last accessed 28th August 2023].

[12] Mehrling, P. (2016) The Economics of Money and Banking, Columbia University, p. 11.

[13] Krüger, S. (2012) Politische Ökonomie des Geldes: Gold, Währung, Zentralbankpolitik und Preise, Hamburg: VSA, p. 115.

[14] Ingham, G. (2004) The Nature of Money, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, p. 4.

[15] Ingham, G. (2020) Money, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, p. 8.