[Work in progress]

Arthur Laffer getting honoured by Donald J. Trump

© EPA

The origin of an unfounded theory:

In the United States, the economic adviser to the then newly elected President Ronald Reagan, Arthur Laffer, made himself a name at the beginning of this new era (of neo-liberalism) by popularising supply-side economics (“Reaganomics”) and theoretical constructs such as the 'Laffer curve' that serve to justify tax cuts for high-income earners and enterprises in general in order to assumingly boost economic performance and activity for the benefit of all market participants. [1]

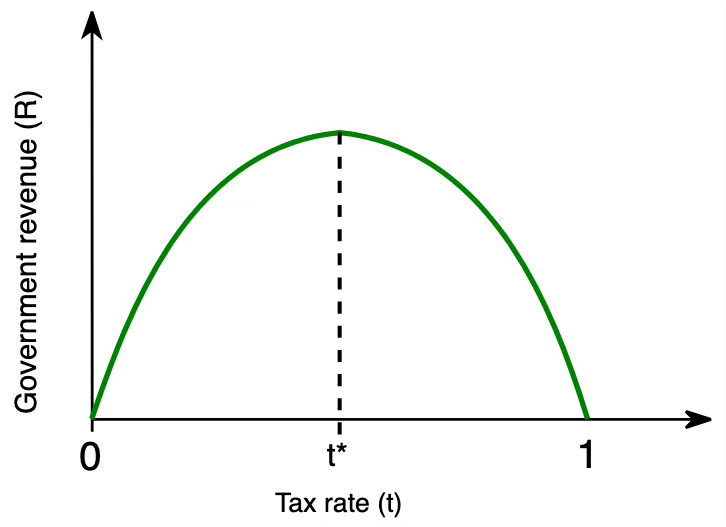

The ‘Laffer curve’

© Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.5

The 'Laffer curve' was used as backing up this theory. It indicates a tradeoff between tax rates and tax revenues while showing seemingly moreover certain tax rates above a threshold mean harm for the general economy and hence decreasing government revenue. [2]

The belief in configuring the tax system in such a way that it is most advantageous for wealthy investors and big business (through mainly lower marginal tax rates) has come to be known and criticised as ‘trickle down economics’ and is commonly associated with the aphorism ‘a rising tide lifts all boats’ as The Wall Street Journal invoked not surprisingly once again nearly a decade after the Great Financial Crash back in September 2008. [3]

Be that as it may, from the 1980s and the 1990s onwards the global economy undeniably ascended ‘as if injected with performance-enhancing steroids’. [4] Those steroids are seen in the academic world as instruments of financial innovation and whose increasing creative deployment rang in another era of financialisation. [5] While global nominal overall economic performance increased only five-fold from US$ 10.1bn in 1980 to around US$ 55.5bn in 2007, nominal global financial wealth accumulated in the same period grew nearly sixteen-fold from US$ 12bn in 1980 to around US$ 197bn almost three decades later, indicating a certain shift in the importance of the financial sector and illustrating the structural outgrowth accumulation of financial assets vis-à-vis the real productivity of the general economy with adjunctive macro-economic management problems. [6]

Taking up the assumption that higher concentration of wealth at the top would lead to more general economic activity (and benefit everyone), this is often referred to in other ways:

“People prefer to talk about ‘competitiveness’ and ‘relief for top performers’. However, this is nothing more than trickle-down economics: tax cuts for high earners are intended to stimulate investment and thus create jobs and prosperity for all.” [7]

Those buzzwords have been frequently utlilised during the Eurocrisis, when fiscal profligacy has been falsely taken as the cause of the Eurocrisis in order to pressure European electorates into ‘structural reforms’ and ‘internal devaluation policies’ as laid out before. All that trickle down economics achieves is to increase economic inequality within societies.

The rising tide does not lift all boats:

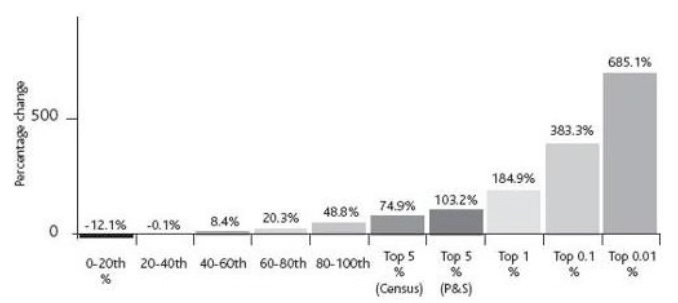

Since the Great Recession the Top 1% largely recovered their losses by capturing up to 95 per cent of income gains in the first three years of the recovery in the United States while the bottom 99%’s incomes stagnated from 2009 through to 2011 and thus had barely started to recover by then. [8]

Change in average household real income in the United States of America, 1979-2012

Note: Data from Census Bureau and Economic Policy Institute compiled by Colin Gordon. Incomes include transfers. Average top incomes (market income only) from Piketty and Saez,World top incomes database. Top 5% figures shown from both sources, http://www.epi.org/blog/growing-growing/.

© Sayer (2015)

It is the Top 0.01% that had the biggest income gain in the United States over the past three decades illustrating moreover that inequalities within the Top 1% are much greater than between the Top 1% and the Bottom 99%. [9] Below table shows a similar picture globally with the growth rate of the top richest world population on average outpacing the average world wealth and income accumulated and earned per adult juxtaposing synchronic cuts in 1987 and 2013.

The growth rate of personal wealth for the top richest population, 1987-2013

Notes: a) Out of 3 billion people in the 1980s and 4.5 billion in 2010. b) Adjusted after inflation rate. Adapted from Piketty (2014, p. 435).

© Beaverstrock & Hay (2016)

This outstanding performance by the Top 1% was much facilitated by the introduction of tax cuts for the wealthy and a number of tax concessions to businesses eventually benefitting a prospering financial sector at the expense of a stagnating productive sector. [10]

Looking at those developments, one will see that:

“what reaches the top stays there. […] Demand is not created by wealth, but by broad purchasing power.” [11]

…

Widening economic inequality:

Germany’s top 0.1 per cent are estimated to possess a staggering €1,647bn, i.e. 17.4 per cent of total wealth of €9,458bn (2014) - the German Top 10 per cent are estimated to own close to two thirds of the country’s total household net wealth (€6,037bn). What is moreover concerning is the sheer lack of wealth in the hands of the bottom half of both populations with the French bottom half being in possession of around only 6.1 per cent (€443bn) and the German bottom half of a mere 2.3 per cent (€214bn). - sources

Sources:

[1] Cantor, V. A., Joines, D. H. and Laffer, A. B. (1981) ‘Tax Rates, Factor Employment, and Market Production’, in Meyer, L. H. (ed.) The Supply-Side Effects of Economic Policy, The Hague: Kluwer.

[2] Laffer, A. B., Moore, S. and Tanous, P. (2008) The end of prosperity: how higher taxes will doom the economy – if we let it happen, New York, NY: Threshold Editions, p. 24.

[3] Kudlow, L. and Domitrovic, B. (2016) ‘Return to JFK’s 'Rising Tide' Model’, in The Wall Street Journal, September 11, [online] available at: <https://www.wsj.com/articles/return-to-jfks-rising-tide-model-1473630982> [Accessed 14 March 2017].

[4] Laffer, A. B., Moore, S. and Tanous, P. (2008) The end of prosperity: how higher taxes will doom the economy – if we let it happen, New York, NY: Threshold Editions, p. 24.

[5] Vercelli, A. (2014) ‘Financialisation in a Long-Run Perspective: An Evolutionary Approach’, in International Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 42(4), pp. 19-46.

[6] Huffschmied, J. (2009) ‘Die Krise der Finanzmärkte und die Antwort der Regierungen’, in Freiwillig in die Krise – reguliert wieder heraus: Die globale Finanzkrise und die Verantwortung von Unternehmen und Banken, [online] available at: <http://www.cora-netz.de/wp-content/uploads/doku_onlineversion.pdf> [Accessed 20 May 2009].

[7] Höfgen, M. (2025) ‘Wohlstand sickert nicht nach unten’, in Surplus - Das Wirtschaftsmagazin, 2nd ed. April 2025, [online] available at: <https://www.surplusmagazin.de/trickle-down-merz-investitionen-steuern/> [Accessed 17 May 2025].

[8] Sayez, E. (2013) Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States (Updated with 2012 preliminary estimates, September 3, [pdf], [online] available at: <http://eml.berkeley.edu//~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2012.pdf> [Accessed 30 March 2017].

[9] Sayer, A. (2015) Why We Can’t Afford the Rich, Bristol: Policy Press.

[10] Magdoff, H. and Sweezy, P. M. (1987) Stagnation and the Financial Explosion, New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

[11] Höfgen, M. (2025) ‘Wohlstand sickert nicht nach unten’, in Surplus - Das Wirtschaftsmagazin, 2nd ed. April 2025, [online] available at: <https://www.surplusmagazin.de/trickle-down-merz-investitionen-steuern/> [Accessed 17 May 2025].

Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the 21st Century, London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Sawyer, M. (2014) ‘What is financialisation?’, in International Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 42(4), pp. 1-18.

Sawyer, M. (2017) ‘Towards de-financialization’, in Ülgen, F. (ed.) Financial Development, Economic Crises and Emerging Market Economies, New York, NY: Routledge.

Beaverstock, J. V. and Hay, I. (2016) ‘They've 'never had it so good': the rise and rise of the super-rich and wealth inequality’, in Beaverstock, J. V. and Hay, I. (eds.) Handbook on Wealth and the Super-Rich, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 1-17