Back to the Basics: European Austerity Revisited

Understanding the saving-investment process via sectoral balances

As was outlined previously, the classic equilibrium of goods model under the so-called ‘commodity paradigm’ could not foresee the Global Financial Crisis of 2008/09.

Shortcomings of the economics profession:

Another explanation for this has been opined by the Financial Times stating that:

“there are other signs of economics turning into an elite closed shop: the handful of journals acting as gatekeepers to career advancement are largely controlled by economists from the same top departments, who also disproportionately pass through the revolving doors into policy making jobs. […] There is no shortage of criticisms to lay at the profession’s door: from its infamous collective failure to spot a global financial crisis in the making and too-slow alarm at inequality or rent-seeking, to its excessive confidence that people act in their informed interest and a huge disconnect between how economists and the general public think about the economy. The question is to what extent such shortcomings are caused by institutional concentration.” [1]

Institutional group-think can be a major factor in the policy sphere when the process of determining an appropriate exit strategy out of an economic recession becomes too limited. The graphs below show Europe’s economic performance vis-à-vis the USA during the last two Global Financial Crises.

Comparison of European and US real GDP per capita in the Global Financial Crises following 1929 and 2007

Note: Year of advent of crises = 100; country composition for Europe includes Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Ireland, Greece, Portugal and Spain; GDP recovered in real terms only by 1940 and as early as 2012 for the case of the US.

Sources: Constructed from Maddison (2006), Eurostat [tsdec100] and Federal Reserve Economic Data.

© Alexander Barta / CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The graphs include the Eurozone’s founding members (excluding Luxembourg, but including Greece) and make apparent that the recovery since the advent of the 2007/08 “Great Recession” has been worse in terms of real per capita GDP compared with the “Great Depression” of 1929 as well as compared with the recovery undertaken by the USA post-2007/08.

Europe’s “lost decade”:

While Europe has experienced a somewhat “lost decade” since 2007 to return to pre-crisis levels only by 2016, their American counterpart achieved the same in about half the time, i.e. 5 years at the most, in 2012. The issue of prolonged recovery in the Eurozone vis-à-vis that of the USA gives an indication for a relatively uncoordinated and dysfunctional intra-European policy coordination and the rather inexperienced policy response on the side of the ECB having raised key interest rates twice rather prematurely in April and July 2011. [3] In defence of the Eurozone, it needs to be noted, however, that public indebtedness by EA-19 (Euro-Area with 19 Member States at the time) grew only by a total of around twenty per cent of GDP while that of the US nearly doubled in the past two decades. Nonetheless is the double-dip recession reducible to the sheer harshness of fiscal consolidation measures [4] which are in turn the consequence of design failures of the Eurozone itself, especially the initial lack of guarantee of the ECB being considered a lender of last resort which in turn happened to trigger self-fulfilling liquidity crises and solvency problems on the side of (semi-)sovereign Member State governments expressed eventually in rising sovereign bond spreads. [5] The entanglement of sovereign refinancing (i.e. net borrowing) and the banking system contributed then again to extensive banking crises which in turn caused the ECB to finally engage in massive liquidity support to the banking systems of the troubled political economies. [6]

In this context, it is necessary to point out that Eurozone’s response to the crisis occurred in the wrong sequence: while the US government first repaired its credit channel by providing massive liquidity support to its troubled banking and financial system through its “Troubled Asset Relief Program” (TARP) and only then used macroeconomic policies, Europe’s monetary policy was being made ineffective by a non-functioning credit channel, despite banks being in Europe in general more central in financing business activities of firms. [7] The Eurozone’s crisis mismanagement based on major misconceptions of the crises did nothing to aid the endogenous convergence of the various growth models but may have instead even cancelled previous gains in territorial cohesion.

Competitivity, balance of payments, sectoral composition/public indebtedness:

When institutional investors mistrusted the Greek State’s ability to auction its government debt securities it resulted in an interest rate spread that in turn threatened the Greek State’s ability to roll over its debt. How could this happen?

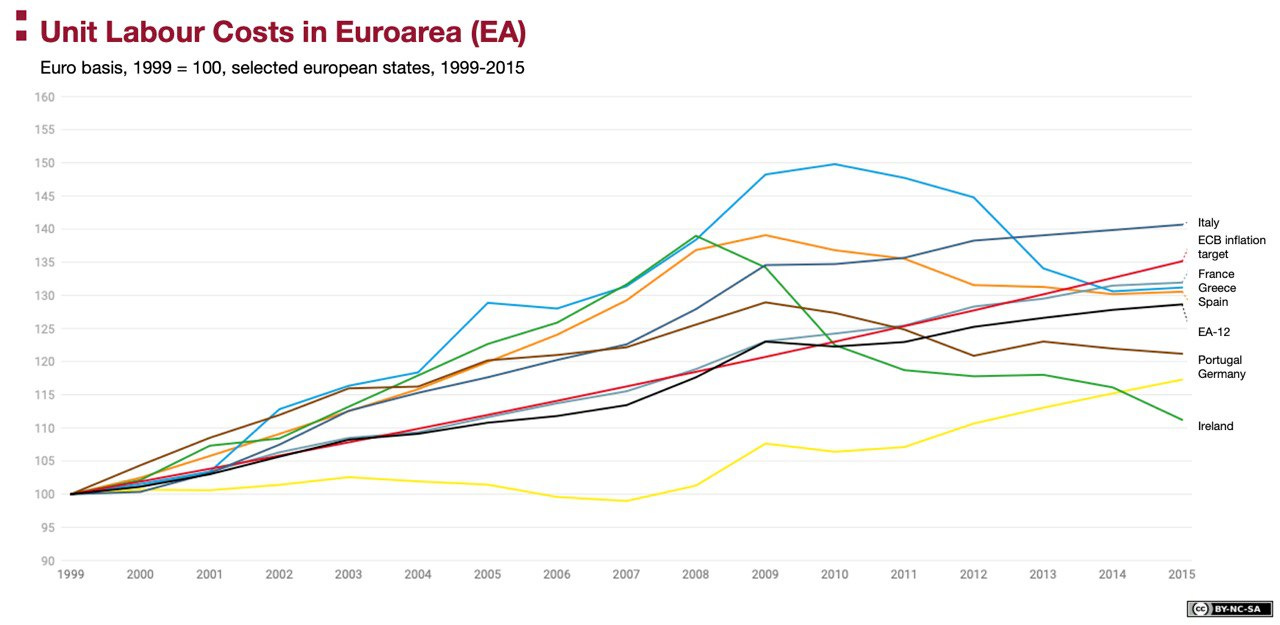

Although the behaviour of banks within the Eurozone were definitely one major factor to exacerbate the crisis, the Eurozone was basically troubled with an asymmetrical development of cost-competitiveness among its Member States. While Greece, Italy, Portugal and Ireland afforded themselves with comparatively higher wages than the rest of the Eurozone, Germany continuously managed to hold wages down since the introduction of the Euro - also due to its Hartz reforms (see figure below). The rationale being that growing worker insecurity contributes to economic growth, as it is assumed to hold inflation expectations low and is deemed favourable for investment. [8] This is problematic, since unit labour costs in each Member State should develop alongside the ECB inflation target (of 2%). [9]

Comparison of Unit Labour Costs in the Eurozone between 1999-2015

Sources: EU Commission (2016), calculations by van Treeck.

© Till van Treeck & Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung / CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The growing difference in competitivity within the Eurozone means that outcompeting national economies develop a current account surplus (= positive balance of payments) compared with the less competitive ones faced in turn with current account deficits.

Average annual current account balance, 1995-2007, 2008-2017 and 1995-2017

Note: Yearly averages in current account balance in per cent of GDP per period; °time-series starting from 1996, §time-series starting from 1999, #time-series starting from 2000, *time-series starting from 2002, †time-series starting from 2003, ‡time-series starting from 2004; Cyprus and Malta not listed due to lack of data availability.

Source: OECD statistics, own calculations.

© Alexander Barta / CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

In other words, those national economies accrueing deficits import more goods and services than they export, whereas their counterparts export more than they import. This means that one national economy’s expenditure is another economy’s income depending on the sectoral composition.

To recap: the Hartz reforms deflated German unit labour costs vis-à-vis France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece, etc., resulting in massive export surpluses for Germany and a slow process of deindustrialisation in the latter. [10]

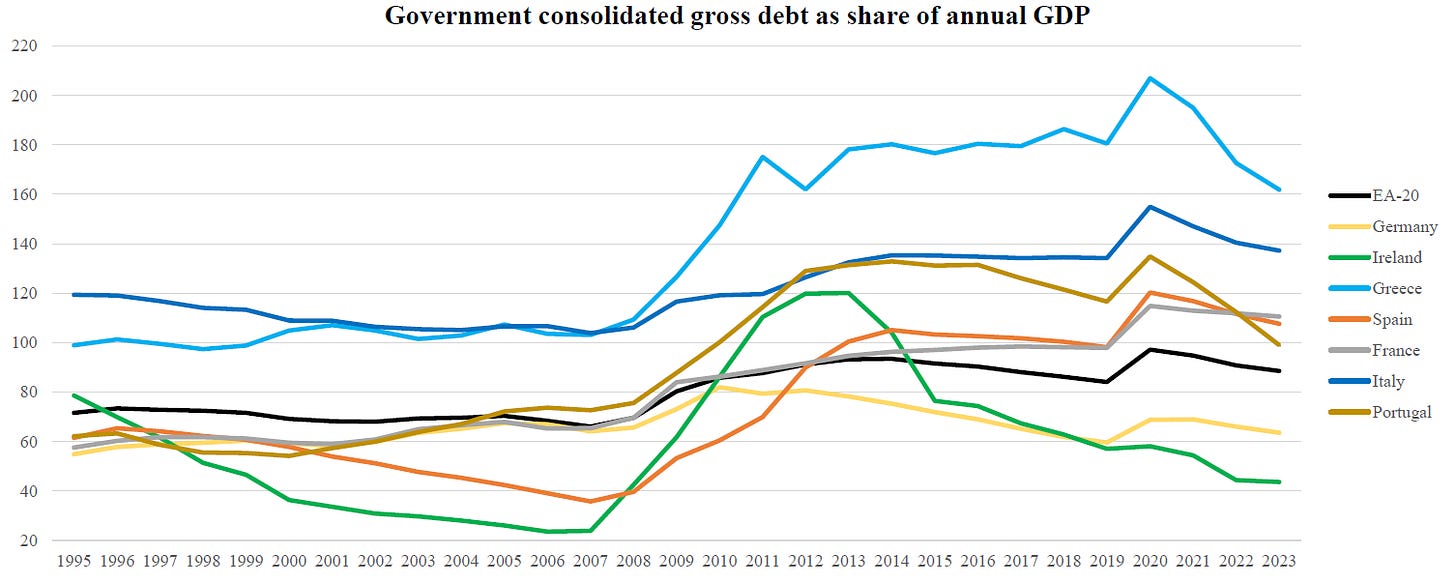

In order to finance imports, deficit countries were being pushed more and more into debt:

Government consolidated gross debt as share of annual GDP, 1995-2023

Source: Eurostat [gov_10dd_edpt1].

© Alexander Barta / CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Austerity policies of internal devaluation:

The prescribed “cure” for increased public indebtedness was austerity alongside “structural reforms” imposed on the deficit countries by the political elites of surplus countries: Greece, for instance, experienced a drop in real wage costs by thirty per cent between 2007 and 2022. [11]

It can be inferred that those internal devaluation policies targeted labour markets to the detriment of employees by facilitating redundancies, weakened the negotiating power of trade unions and so strengthened the already structurally dominant position of employers. [12] In sum, the burden of imbalances rested pre-dominantly on deficit countries alone, repressing wages and eventually domestic demand in these countries. That the combination of internal devaluation in the Southern deficit countries and internal revaluation in the Northern surplus countries would have reasonably balanced the Eurozone’s path out of the crisis but was through the imposition of fiscal discipline and austerity, by explicitly the German Government, deemed unacceptable and appears to have definitely vigorated a certain bias in favour of export-led growth unequivocally underpinning the design of the Eurozone. [13]

Europe’s “lost decade” can thus be explained by:

institutional group-think in the discipline of economics

wrong assessment of root causes of the crisis

ideological policy mix resulting in a politics of austerity

The “paradox of thrift”:

The sectoral balances of the government fiscal balance, the private sector (i.e. private households and businesses) and the “foreign sector” (i.e. current account balances = “rest of the world”) must, by definition, always even out. One sector’s saving (surplus) is another sector’s debt (deficit).

Sectoral Financial Balances in U.S. Economy 1990-2012

Source: FRED, BEA Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts.

© Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) / CC BY-SA 3.0

In the USA the foreign sector surplus and private sector surplus have been offset by a government budget deficit since 2008. In the Eurozone, Germany has developed a private sector surplus, a negligable government fiscal balance and shifted this way its sectoral balance to the rest of the world (i.e. incl. the rest of the Eurozone):

“For someone to benefit from a reduction in wages (becoming more cost-competitive), there must be someone else who is willing to spend money on what that person produces. John Maynard Keynes rightly referred to this as “the paradox of thrift”: if we all save at once there is no consumption to stimulate investment.” [14]

A politics of austerity (i.e. fiscal consolidation = public investment restraint = a form of saving) withdraws money from the economic cycle and hence explains the different economic recoveries since the Global Financial Crisis in the USA and Europe.

Once governments restrain public expenditure through austerity policies, their economies are prone to become less active. Since the calculation of the gross domestic product consists of the following components:

GDP = household + investment + government + net exports, [15]

a significant drop in government expenditure (= fiscal consolidation) will likely mean a negative impact on total economic output. In the case of Germany, the lack of public expenditure has been offset by the foreign sector. In the rest of the Eurozone, esp. in the crisis affected deficit countries like Greece, Portugal, Italy and Spain, the one sector compensating for the net saving sectors has been mainly the state itself (as the only significant net borrower). In essence, there has then occurred a massive transformation of private, financial debt for public debt over the course of the so-called Eurocrisis. Labelling it a “sovereign debt crisis” as it was commonly being framed in public discourse is missing the fact that it was the financial sector causing the crises cascades in the first instance.

Sources:

[1] The FT View (2024) ‘Is economics in need of trustbusting?’, in Financial Times Weekend, 31 August/1 September, p. 6, also [online] available at: <https://www.ft.com/content/d973dc8c-b1a1-4dd1-bd4e-be6225494ded> [Last accessed 28th September 2024].

[2] Maddison, A. (2006) The World Economy, Paris: OECD Publishing, [online] available at: <http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/Maddison2001Data.pdf> [Last accessed 14th June 2017].

[3] ECB (2012) Annual Report 2011, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, [pdf], [online] available at: <https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/annrep/ar2011en.pdf> [Last accessed 16th May 2018].

[4] Heimberger, P. (2017) ‘Did fiscal consolidation cause the double-dip recession in the euro area?’, in Review of Keynesian Economics, Vol. 5(3), pp. 439-458.

[5] De Grauwe, P. and Ji, Y. (2015) ‘Correcting for the Eurozone Design Failures: The Role of the ECB’, in Journal of European Integration, Vol. 37(7), pp. 739-754.

[6] Giavazzi, F. and Wyplosz, C. (2015) ‘EMU: Old Flaws Revisited’, in Journal of European Integration, Vol. 37(7), pp. 723-737.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Federal Reserve Board (1997) ‘Testimony of Chairman Alan Greenspan before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate February 26, 1997, in The Federal Reserve's semiannual monetary policy report, [online] available at: <https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/hh/1997/february/testimony.htm> [Last accessed 14th September 2024].

[9] Di Carlo, D. and Hoepner, M. (2022) ‘Germany is likely to shift toward wage restraint as inflation concerns mount’, in LSE Blog, [online] available at: <https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2022/07/25/germany-is-likely-to-shift-toward-wage-restraint-as-inflation-concerns-mount/> [Last accessed 15th September 2024].

[10] compare Amable, B. (2016) ‘The Political Economy of the Neoliberal Transformation of French Industrial Relations’, in ILR Review, Vol. 69(3), pp. 523-550.

[11] Romei, V. (2024) ‘Greece’s economic rebound in (painful) context’, in Financial Times, [online] available at: <https://www.ft.com/content/ba7e18ea-eaf4-4104-bbe7-bb7f97d182e5> [Last accessed 15th September 2024].

[12] Witte, L. (2012) ‘Austerity Policy in Europe: Spain’, in FES International Policy Analysis, August 2012, [pdf], [online] available at: <http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id-moe/09336-20121119.pdf> [Last accessed 21st July 2018]; Castro Caldas, J. (2012) ‘The Consequences of Austerity Policies in Portugal’, in FES International Policy Analysis, August 2012, [pdf], [online] available at: <http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id-moe/09311.pdf> [Last accessed 21st July 2018]; Boukalas, C. and Müller, J. (2015) ‘Un-doing Labour in Greece: Memoranda, Workfare and Eurozone 'Competitiveness'’, in Global Labour Journal, Vol. 6(3), pp. 390-405.

[13] Johnston, A. and Regan, A. (2018) ‘Introduction: Is the European Union Capable of Integrating Diverse Models of Capitalism?’, in New Political Economy, Vol. 23(2), pp. 145-159.

[14] Blyth, M. (2013) Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, p. 22.

[15] Bank of England (2019) ‘What is GDP?’, [online] available at: <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/explainers/what-is-gdp> [Last accessed 15th September 2024].