Sovereign indebtedness is one of the most concerning issues in the political arena, and a very contested one at that. Understanding sovereign indebtedness is thus not only key for making sense of public finance, i.e. ‘the study of the role of government in the economy.’ [1] It also affects fiscal policy, i.e. ‘decisions about government spending and taxation.’ [2]

What are Sovereign Debt?

Sovereign debt ‘are the accumulated liabilities of the general government incurred by annual 'deficit spending' to finance the public budget and expenditures.’ [3]

With deficit spending is meant that governments may finance budget deficits by borrowing: budget deficits being defined as ‘the excess of government expenditures over tax revenues for a particular time period, typically a year.’ [4] In other words, sovereign or public debt is the sum of annually incurred budget deficits over the long run. This seems rather straightforward. What is, however, contested are

“the actual mechanics of government expenditure, debt management and its relation to the wider monetary and financial system.” [5]

Furthermore, there is less attention given to the circumstance that

“[g]overnment debt is in fact indispensable for the functioning of financial markets because banks and other financial institutions not only invest in it but also use it as a guarantee (collateral) for borrowing more. For this, government debt must be equivalent to money; that is, it must be a very liquid asset that can be rapidly and securely exchanged. To guarantee the stability of the monetary and financial system, the central bank must therefore act in such a way that government debt and money are almost indistinguishable from one another.” [6]

The following graph shows the historical development of the level of sovereign indebtedness for selected countries and advanced economic areas between 1800 and 2015:

The level of sovereign indebtedness has on average significantly increased in this time for the USA and Germany, whereas the volatility of the respective debt burden for the UK, France, Italy and Spain seems rather high. The graph also shows the upper limit of 60% for the debt to GDP ratio as agreed in the Maastricht Treaty for EU member states. Nearly all selected countries have breached this arbitrarily defined threshold with the onset of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008/09. Only Germany has recently managed to decrease its total sovereign indebtedness to the level the European Treaties prescribe through its current account surpluses accumulated via its export-oriented growth model. [7] Germany is, moreover, violating the so-called ‘golden rule of fiscal policy’, as its self-imposed and constitutionally enshrined ‘debt brake’ did since its implementation in 2009 no longer allow for the usage of low, long-term interest rate levels for loan-financed public investment programmes: [8]

“Despite all the differences between the paradigmatic approaches in details and in their economic policy implications, the economic community across all schools of economics agree that the structure of public expenditure is of great importance ('structure matters') and that investment-orientated indebtedness on the part of public budgets — within the framework of sustainability — is therefore not only permissible but even advisable in terms of optimising growth, employment and (burden) distribution.” [9]

Although the empirics seem to indicate that public debt in itself does not inhibit economic growth prospects and that more attention needs to be paid for the structure of public finance and the effects of fiscal policy, the political symbolism of sound fiscal policy and the obsession for budget consolidation and the ‘zero deficit’ may merely be the means to curtail government activity as a goal. [10]

The crux: the composition of public debt

The level of indebtedness does not seem to be the main issue in this respect. Critical is the composition of sovereign debt. A country can issue sovereign debt securities in its own currency or emits its government bonds, accepts bank loans, establishes a source of funding from international capital markets, in a foreign currency. A distinction should hence be made

“between a sovereign issuer of the currency from its non-sovereign user(s).” [11]

The latter faces the problem that if imported capital does not initiate any growth effects, no additional resources are being generated to hold the country’s debt service burden sustainable — resulting in a ‘debt overhang’ or even impending insolvency. [12]

In contrast to the non-sovereign users,

“governments that issue their sovereign currency are not subject to a budget constraint as traditionally conceived. As issuers of currency, governments can always buy what is for sale in their currency. They do not and cannot rely on tax revenue to finance their spending. The amount of output for sale in the country’s currency, its real resource space, rather than the government’s financial capacity, is what constrains government’s spending. When total spending in the economy is insufficient, real resources, such as labor, are left idle. Alternatively, if total spending in the economy exceeds the economy’s potential to produce real goods and services, this may result in inflation.” [13] (own emphasis)

Ways of state revenue

Empirically, the modern state

“has not one but four principal ways to finance itself.

It can extract money from its citizens;

it can create money by going into debt;

it can earn money (for instance by exploiting natural resources) or

it can mobilise money from the outside (for example by colonial extraction or conquest).

The modern state can be a tax state, a debt state, a rentier state or a predator state. Across time and place, the public finances of most modern states comprise a combination of these sources of income. […] A constant flow of revenue is a precondition for the modern state to create and maintain its monopoly of physical violence, its legitimacy and its external security (Weber, 1994). Without revenue, the state cannot exist. […] The state is built around the power relationships between the government, taxpayers and the state’s financiers.” [14] (own emphasis)

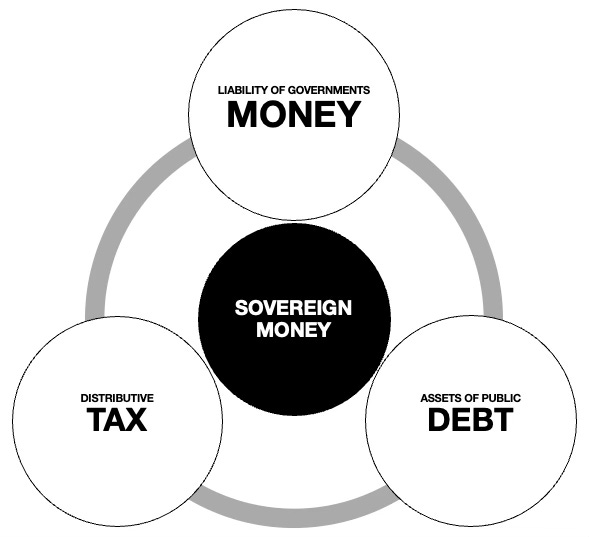

It is therefore plausible to put forward a chartist explanation for ‘sovereign money’ money that is central to this power relationship. [15]

The state as a negotiator between tax payers and financiers

The cycle between money, tax and debt

“is best understood if we look at it from the perspective of a balance sheet. The government creates money by going into debt. There is no other way to create sovereign money: The government prints notes, mints coins and, much more importantly today, sells government bonds. The issuing of notes, coins or government bonds is a liability on the government’s balance sheet. […] A government can only create money by going into debt if it has an asset on the other side of its balance sheet. Otherwise, no creditor (small or large) would be willing to extend credit to the government. These assets are the citizens’ tax debt. […] By exclusively accepting the money that the state itself issues as a means to discharge tax debt, the state ensures its monopoly power over sovereign money creation. […] The cycle closes where the state’s financiers extend credit to the government only if there is a valid money that can reliably account for how much the government owes them. The cycle of money, tax and debt underpins the struggle between the government, taxpayers and financiers over how to fund the state. This struggle is fundamental to the state’s legitimacy, because the expectations of taxpayers are irreconcilable with those of financiers. Taxpayers expect public goods in return for their payments; corporate taxpayers hope for low interest rates and favourable bankruptcy laws in order to sustain company financing. Financiers, on the other hand, request that tax money be spent on serving interest payments and debt. They aim for interest rates that make their lending profitable and for laws that punish default. That is, public finance is a source of state power and, at the same time, a site of conflict and contestation between different groups in society over their material interests. In this conflict, the government cannot fulfil the material interests of all groups simultaneously. It has to prioritise some over others. As a result, the modern state faces, to cite Helen Thompson (2010, p. 147) its ‘fundamental political problem of legitimating rule’. To create and extract money legitimately, the government has to negotiate successfully the debtor-creditor relations created by the cycle of sovereign money creation, tax and debt (Ingham, 2004; Vogl, 2015). The relationship between the government, the taxpayers and financiers is institutionalised in a country’s tax and banking systems. The tax system is the institutional expression of the power relationship between the government and the taxpayers. It articulates who has to pay how much on the basis of which principles. The banking system is the institutional expression of the power relationship between the government and its financiers. It articulates who creates credit, who has access to credit and under which conditions. The central bank plays, indeed, a central role in that power relationship. A central bank makes it possible for financiers to extend private credit to the state. At the same time, creating central bank reserves through the issuing of government bonds, the state is – since Bagehot’s days – the ‘lender of last resort’ to its own financiers (Mehrling, 2011; Vogl, 2015). Yet, as Weber (1994) points out, the state controls, but does not own, these resources. Public finances therefore make the state dependent on those who hold the ownership of the resources: financiers in the case of debt and taxpayers in the case of tax. The borrowing and taxing by the state are hence an expression of, and a limit to, its power (Ingham, 2004; Vogl, 2015). The power position of the government in its relations with financiers and taxpayers depends on its ability to successfully mediate the central political conflict about how the costs and benefits of tax and debt are distributed between different groups of society (Calomiris and Haber, 2014; Levi, 1989).” [16] (own emphasis)

Conclusive Remarks

States do not finance themselves exclusively from tax revenues, but have the option of regularly issuing bonds and thus tying up the necessary funds on the capital market in order to invest in public infrastructure and services of general interest. In times of non-crisis, this approach increases economic activity, combats unemployment and relativises the level of public debt.

The level of sovereign debt is not a problem in itself, as long as the debt is nominated in the government’s own currency. What is hence crucial is the composition of public debt and the distinction between sovereign issuers of money and non-sovereign users.

This means that for sovereign issuers of debt there is not a sustainability problem (and therefore a ‘budget constraint’), but there is merely a constraint of real resources if the economic potential is not exhausted.

The state creates money by issuing debt and reflects a liability to the government. Debt securities (government bonds) are assets in the non-public sphere and are hold by private institutional investors, financiers, and are expressed in the social and physical infrastructure the state’s citizens afford themselves. Public debt and private wealth are entangled. These assets are also the citizens’ tax debt, as the state ensures by way of taxation that its sovereign currency remains central and monopolistic (as opposed to cryptocurrency).

Problematic is rather the struggle between the government, taxpayers and financiers over how to fund the state.

Sources:

[1] Gruber, J. (2019) Public Finance and Public Policy, 6th ed., New York, NY: Worth Publishers, p. 3.

[2] Mishkin, F. S. (2013) The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets, 10th ed., Essex, UK: Pearson, p. 53.

[3] Ali Abbas, S.M. & Pienkowski, A., (2022) ‘What Is Sovereign Debt?’, in IMF Finance & Development, pp. 60-61.

[4] Mishkin, F. S. (2013) The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets, 10th ed., Essex, UK: Pearson, p. 53.

[5] Berkeley, A., Ryan-Collins, J., Voldsgaard, A., Tye, R. & Wilson, N. (2024) ‘The self-financing state: an institutional analysis of government expenditure, revenue collection and debt issuance operations in the United Kingdom’, [online] available at: <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4890683> [Last accessed on 25th July 2024].

[6] Monnet, E. (2024) Balance of Power: Central Banks and the Fate of Democracies, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, pp. 23f.

[7] Flassbeck, H. (2024) Grundlagen einer relevanten Ökonomik, Neu-Isenburg: Westend, p. 219.

[8] Bofinger, P. (2020) Grundzüge der Volkswirtschaftslehre, 5th ed., München: Pearson, p. 369.

[9] Heise, A. (2002) ‘Zur ökononomischen Sinnhaftigkeit von ,Null-Defiziten'‘, in Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 28. Jahrgang, Vol. 3, p. 304.

[10] Ibid., p. 292.

[11] Kelton, S. (2011) ‘Limitations of the Government Budget Constraint: Users vs. Issuers of the Currency’, in Panoeconomicus, Vol. (1), p. 60.

[12] Schularick, M. (2006) Finanzielle Globalisierung in historischer Perspektive, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, p. 121.

[13] Nersisyan, Y. (2024) ‘Resource Constraints and Economic Policy’, in Working Paper No. 1065, Levy Economics Institute, [online] available at: <https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_1065.pdf> [Last accessed on 18th December 2024].

[14] Binder, A. (2019) The politics of the invisible: Offshore finance and state power, Dissertation, University of Cambridge, p. 3, [online] available at: <https://web.archive.org/web/20220127081824/https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/294713/Binder%20(2019)%20Offshore%20finance%20and%20state%20power.pdf;jsessionid=67B68D75C87647DF349052E3F826DA8F?sequence=1> [Last accessed on 18th December 2024].

[15] Ingham, G. (2004) The Nature of Money, Cambridge: Polity, p. 112.

[16] Binder, A. (2019) The politics of the invisible: Offshore finance and state power, Dissertation, University of Cambridge, p. 3, [online] available at: <https://web.archive.org/web/20220127081824/https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/294713/Binder%20(2019)%20Offshore%20finance%20and%20state%20power.pdf;jsessionid=67B68D75C87647DF349052E3F826DA8F?sequence=1> [Last accessed on 18th December 2024].