Evolution of Systems of Knowledge [Part I]

A brief genealogy of specialised knowledge systems

With the great transformation from feudalist to modern-capitalistic social relations that ensued with the European Enlightenment and more intensively with the onset of industrialisation a critical conjuncture emerged between what was once the theological sphere and providence of the divine or a general religious and aesthetic human quest such as Aristotle’s conception of εὐδαιμονία, “human flourishing” [1], and the gradual genesis of the modern sciences of labour, life and language, which began themselves with the ambitious attempt to ‘define the autonomy of nature’: [2] with the first scientific revolution at the turn of the 16th century, which saw the separation of natural philosophy into new mathematically and experimentally oriented branches, as well as the second revolution around the turn of the 18th century with the formation of scientific disciplines. [3] Notwithstanding it is still not acknowledged if the thesis of a real conceptual and epistemic break coterminous with the revolutionary development of technological and political practices usually associated with the advent of modernity holds true. [4]

Emancipation from theological and philosophical mechanisms of control:

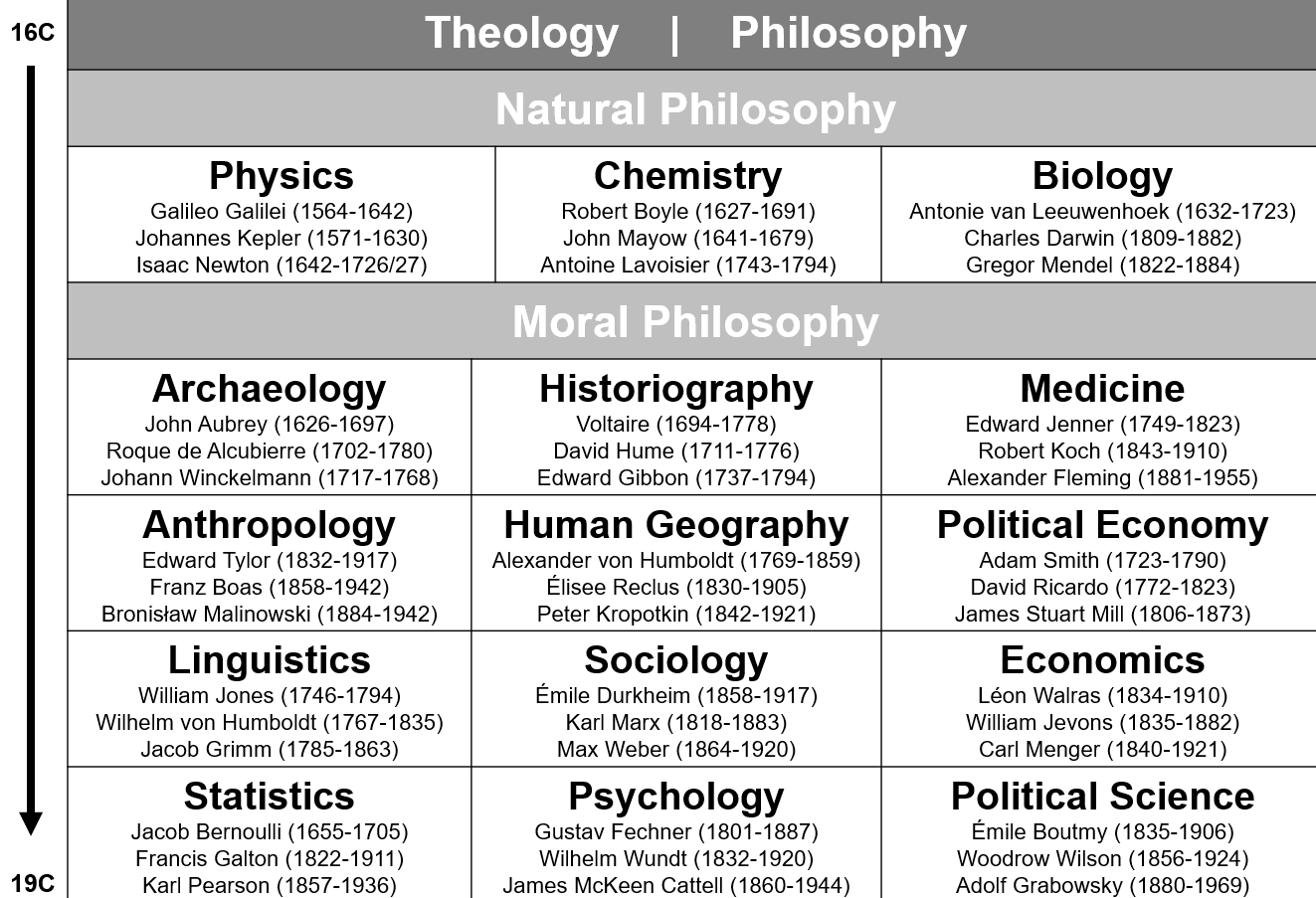

The metamorphosis of “natural philosophy” into distinct scientific disciplines such as “physics”, “chemistry” and “biology” self-evidently progressed, kickstarting this way interactively a ‘great transition’ [5] denoting a process of overall academic specialisation and professionalisation of new fields of inquiry, in other words ‘a more differentiated constellation of intellectual practices’ and their institutionalisation as faculties at universities in order to facilitate the transmission of such specialised knowledge in retrospect. [6] In this vain, what used to be the domain of “moral philosophy” turned into distinct fields of inquiry such as “anthropology”, “(political) economics”, “political science” and “sociology”. [7] This transformation is more complex than this simple formulation suggests. Before those mentioned fields of knowledge were becoming all the more distinct from each other, there was a period of transition in which “moral philosophy” opened up the more integral system of thought called “social science”. This transition can be dated from 1738 with Voltaire’s Essai sur la Philosophie Newtonienne and culminated in the works of and the circle around Condorcet who came to coin the term “science sociale” in the 1790s. [8] Those Frenchmen may have considerably contributed to the academic institutionalisation of social science. [9] The most supreme intellectual endeavours of “philosophy” and “theology” tended likewise to be assigned separate roles and new boundaries. [10] The below figure depicts a selective sketch exhibiting the disintegration of the order of knowledge with the advancement of modernity:

There has eventually emerged a decentralised system of scientific disciplines preventing the possibility of any real supra-disciplinary control mechanisms. [11] Historically this function was adopted by theology and subsequently philosophy, but soon enough the various scientific disciplines no longer accepted such external intrusion into their subjects of expertise and established their own ethical boundaries, modes of scientific education and reward systems, though the forms of institutionalisation differed not only within the disciplines themselves but also nationally, giving rise to various national traditions. [12] By the mid-19th century academic practice can be seen as being dispersed as a consequence of class politics of capitalist discipline. [13]

According to Herbst (2014) reviewing the work of Ben-David,

“[s]cientific growth manifested itself by a number of related —co-evolutionary— developments:

● the geographic diffusion, propagation and dispersion of science, i.e., the growth in the number of higher education institutions and an associated growth in the number of faculty positions, or enrollments of students, in given fields;

● the disciplinary differentiation and diversification, and the growth in the number of academic—disciplinary—fields” [14]

German “Humboldtian” system of knowledge production:

The most fertile ground for this evolution to gain pace has been identified in the cultural sphere of Prussia and Austria-Hungary where a proliferation of polytechnic institutions endowed with professional staff were the ideal hosts for the diffusion of research and the formation of new academic foci or disciplines in a competitive regional setting. [15] In fact, the German—Humboldtian—university model became a kind of archetype that was to be emulated elsewhere in the 19th and early 20th centuries. [16] Noteworthy is the observation of ‘the fact that Germany alone produce[d] more [research] than the rest of the world together’ and the country’s ‘scientific hegemony’ at the turn to the 20th century must be recognised ‘in all fields’. [17]

Proliferation of US American “specialised” system of knowledge production:

Though the German comparative advantage vis-à-vis French and British universities came to an end eventually at the beginning of the 20th century with the lack of funding or the willingness to fund. [18] This is when US American educational macrostructure crystallised and its academic labour market was fundamentally undergoing changes as ‘businessmen and bankers [were] to displace clergymen from their seats on university boards, imposing their own limits to what could be legitimately taught’: limiting the range of academic freedom by changing the production conditions of knowledge through further academic specialisation was key to attuning scientific research closer to the needs of the interests of power and business. [19] In other words, philosophical anchorage of scientific debate was being sidestepped by adopting ‘a focus on epistemology and method’ instead, the American higher education model proliferating after the end of the Second World War globally [20]:

“It can be argued that this decentralized institutional structure was itself responsible for the scientistic orientation of American social science. In Europe, the social science disciplines were kept in close touch with philosophy and history through subordinate appointments and controlled examination systems. In American universities they were freed from traditional ties and able to drift toward the magnet of modern knowledge, natural science.” [21]

The social nature of knowledge production:

The positivist attempt to anchor social science disciplines in the rational methodological practices of the natural sciences has the objective to give legitimacy to their scientific output. Further does the disembeddedness from an ethical feedback loop seem to be excused by the utilisation of such knowledge for the advancement of technology. Social science, however, does not concern itself with natural objects but with social relations. Social scientific knowledge is hence socially constructed:

“Once we recognize the essentially social nature of scientific activity, we are compelled to see both the ‘context of discovery’ and the ‘context of justification’ in a different light. The context of discovery is in fact a context of construction, of theories, of instruments, and also of evidence. […] [D]ata that appear[s] in the pages of […] journals are no less a product of the constructive ingenuity of their authors than are the instruments and the theoretical hypotheses; they are not raw facts of nature but are elaborately constructed artefacts. However, these artefacts are constructed according to explicit rational schemes accepted within a certain community of investigators. […] [I]nvestigative practice is very much a social practice, in the sense that the individual investigator acts within a framework determined by the potential consumers of the products of his or her research and by the traditions of acceptable practice prevailing in the field.” [22]

Sources:

[1] Edelstein, L. (1952) ‘Recent trends in the interpretation of ancient science’, in Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 13(4), pp. 573-604; Edelstein, L. (1961) ‘Motives and incentives for science in antiquity’, in Crombie, A. C. (ed.) Scientific change: Historical studies in the intellectual, social and technical conditions for scientific discovery and technical innovation, from antiquity to present, London: Heinemann Educational Books, pp. 15-42.

[2] Foucault, M. (1994) The order of things: An archeology of the human sciences, New York, NY: Random House, p. 126.

[3] Cunningham, A. and Jardine, N. (1990) Romanticism and the sciences, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[4] Wittrock, B., Heilbron, J. and Magnusson, L. (1998) ‘The rise of the social sciences and the formation of modernity’, in Heilbron, J., Magnusson, L. and Wittrock, B. (eds.) The rise of the social sciences and the formation of modernity: Conceptual change in context, 1750-1850, Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, p. 2.

[5] Turner, R. S. (1987) ‘The great transition and the social patterns of German science’, in Minerva, Vol. 25, pp. 56-76.

[6] Wittrock, B., Heilbron, J. and Magnusson, L. (1998) ‘The rise of the social sciences and the formation of modernity’, in Heilbron, J., Magnusson, L. and Wittrock, B. (eds.) The rise of the social sciences and the formation of modernity: Conceptual change in context, 1750-1850, Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, p. 2f.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ben-David, J. (1978) ‘The structure and function of nineteenth-century social science’, in Forbes, E. G., (ed.) Human implications of scientific advance: Proceedings of the XVth international congress of the history of science, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; Head, M. (1982) ‘The origins of "la science sociale" in France, 1770-1800’, in Austrialian Journal of French Studies, Vol. 19(2), pp. 115-132.

[10] Rorty, R. (1979) Philosophy and the mirror of nature, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; Collins, R. (1987) ‘A micro-macro theory of intellectual creativity: the case of German idealist philosophy’, in Sociological Theory, Vol. 5, pp. 47-69.

[11] Stichweh, R. (1984) Zur Entstehung des modernen Systems wissenschaftlicher Disziplinen: Physik in Deutschland 1746-1890, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

[12] Ibid.

[13] van der Pijl, K. (2015) ‘Global political economy and the separation of academic disciplines’, in Fouskas, V. K. (ed.) The politics of international political economy: A survey, New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 3-19.

[14] Herbst, M. (2014) ‘Academic organization and scientific productivity’, in Herbst, M. (ed.) The institution of science and the science of institutions, Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 15-35.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Schwinges, R. C. (2001) Humboldt International: Der Export des deutschen Universitätsmodells im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Vol. 3 of Veröffentlichungen der Gesellschaft für Universitäts- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Basel: Schwabe & Co.

[17] Lot, F. (1892) L’Ensignement supérieur en France: ce qu’il est, ce qu’il devrait être, Paris: H. Welter, p. 30, cited by Paulsen, F. (1902) Die deutschen Universitäten, Berlin: A. Asher & Co. p. 210, cited by Herbst, M. (2014) ‘Academic organization and scientific productivity’, in Herbst, M. (ed.) The institution of science, p. 20.

[18] Herbst, M. (2014) ‘Academic organization and scientific productivity’, in Herbst, M. (ed.) The institution of science and the science of institutions, Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 15-35.

[19] van der Pijl, K. (2015) ‘Global political economy and the separation of academic disciplines’, in Fouskas, V. K. (ed.) The politics of international political economy: A survey, New York, NY: Routledge, p. 10f.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ross, D. (1991) The origins of American social science, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 161.

[22] compare Danziger, K. (1990) Constructing the Subject: Historical origins of psychological research, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p. 3f.